Kallipygos (Καλλίπυγος)

Having beautiful buttocks

Exhibit A

Exhibit B

Source

Also a fantastic .gif of this scene by the lovely Circusgifs on tumblr

Exhibit C

Questions?

Kallipygos (Καλλίπυγος)

Having beautiful buttocks

Exhibit A

Exhibit B

Source

Also a fantastic .gif of this scene by the lovely Circusgifs on tumblr

Exhibit C

Questions?

I hope 2016 is progressing decently for everyone in Armitageworld… Personally, I have decided that in 2016, we will be postponing Christmas until after Christmas. Honestly – the holiday season was just this side of grueling. On the plus side though – my iPad has been emancipated from MiniMe’s clutches since Santa delivered her new Chromebook. Hurray – I can watch Netflix in peace again!

With all of my current TV streams on winter hiatus, I returned to an old haunt – Robin Hood, and was struck again by how effectively Richard Armitage (as Guy of Gisborne) can deploy full scale seduction. I just finished Season 1, and am again left wondering how Marian resisted a couple of those seductive salvos. For me, the most effective persuasive instrument that Sir Guy utilizes is his voice.

Don’t get me wrong…the physical package is plenty potent, overwhelmingly so in some instances. In combination with an almost groaned syllable or a throaty whisper?

*Boom*

Robin Hood S1 E11

Source

Here, having declared himself to her, Sir Guy presses his suit…his voice becoming deeper, but softer

“I want to know you.”

Before groaning,

“Marian!”

and then a barely audible,

“be with me!”

*Ahem*

For all that Sir Guy, especially under the influence of the Sheriff, is often brutal, and perhaps even dishonorable, Richard Armitage brings a seductive force to him that is impossible to overlook. Even the unyielding Marian seems to be wavering in the last few episodes of Season 1.

Robin Hood S1 E13

Source

A breathy

“Stay!”

after another declaration of passion and a brief kiss hit me straight in the feels

maybe it affected Marian similarly and she fled for self preservation…

In his pursuit of Lady Marian, Richard Armitage’s Sir Guy seems to be compellingly channeling more than a bit of Πειθώ. Peitho, the personification of persuasion and seduction, is a rather shadowy figure in the Greek Pantheon. Although she also appears as a rhetorical concept, in myth, Peitho is most commonly understood as one of the daughters and frequent companions of the goddess Aphrodite.

In this marble frieze, Peitho, seated a top a column, directs the discourse between Aphrodite and Helen, seated beneath her, and Eros and Paris. The seduction of Helen, she who launched a thousand ships, by the Trojan prince Paris is one of the “great” love stories in classical myth. (if one discounts that it was all set in motion by a sneaky goddess to win a bet with two other goddesses and resulted in a brutal war that lasted 10 years)

Seduction/persuasion are rather interesting concepts in ancient Greek. That is, there is a VERY fine line between seduction and rape in most literary accounts. In fact, in many cases, the words are used interchangably in a context where women had almost no power to object in any meaningful way. Equally interesting is how Peitho, seduction personified, is depicted in myth.

#seductionfail

Source

When the allure of seduction fails and gives way to force, as in the above scene, Peitho is typically depicted as fleeing the scene…that is, at least to some degree, the Greeks recognized the difference between enticement and overt force. So too did Sir Guy…for the most part. In both of the scenes above, Marian rebuffs Guy’s tempting advances, and in each instance, Guy resists the urge to force her. He is definitely trying to win her over, he is frequently coercive, but he stops short of force. It seems that Peitho is still hanging around. For now…

Given that I am almost never the first person to hear about Richard Armitage related news, I’m going to assume that everyone is aware of his new project, Sleepwalker…reportedly a suspenseful film about a somnambulist (Ahna O’Reilly) in which Richard Armitage plays a doctor specializing in sleep disorders. The subject of this film called to mind several things. One is that I need to have a sleep study done, but I have been putting it off…in part because of my schedule, but also because I am slightly uneasy with the vulnerability aspect of it all. The notion of having people observe me while I’m asleep and not aware of my actions unnerves me quite a bit.

More interestingly, it got me thinking about how stories of sleep manifest in classical myth. The Greek god Hypnos (Somnus in Latin) governed sleep…he was generally considered a benevolent deity who gifted mankind with the renewing benefits of sleep. There is not a terrible lot of mythology surrounding this rather minor god, but there are several really interesting myths centered around a sleeping figure. One of my favorites is the story of Endymion and Selene.

Like most Greek myths, there are variations to the story depending on which ancient source one reads. This is a fact that is always kind of confusing to my students, who really seem to want there to be one right version of everything. Ancient culture is rarely so simple. It’s not particularly hard to see how variations in the myths evolved. The Greeks had literacy (such as it existed in most of the ancient world) in the late Bronze Age, but then it was lost from about 1100 – 800 BC. This means that mythological stories would have been transmitted orally during those centuries. Oral traditions preserve the basic framework of stories very well, but it is not unusual for the details to vary from place to place over the centuries…kind of like the modern idiom of a “fish story” where the details change a bit every time the fisherman tells the tale.

Way back when in a course called Classical Mythology I learned the myth of Selene and Endymion following the version recounted by Apollonios of Rhodes which reads rather like a fairy tale…

Once upon a time, Selene, the goddess of the moon fell in love with a beautiful mortal named Endymion. She loved him so much that she asked his father Zeus to grant him eternal youth so that Endymion could stay with her forever. Zeus granted her wish, but there was a catch…he placed the youth into an eternal sleep. Endymion would be eternally youthful and beautiful, but he would also be eternally asleep.

Selene & Endymion

by Giovanni Antonio Pellegrini

Source

Apparently, this everlasting slumber wasn’t much of an obstacle to Selene’s love for him. The story goes on to recount that she visited her sleeping beloved every night and the two of them had fifty daughters.

Good gravy – where to start with this one?! Firstly, this version of the story is a perfect example of the English idiom, “be careful what you wish for…” or at least be very specific. The Greek gods had a tendency to be extremely capricious when granting this sort of wish (I’ve heard similar tales of the caprice of genies and leprachauns…you just can’t trust supernatural wish granters I guess!) It’s fairly obvious that Selene might have preferred that Endymion be eternally youthful and awake, but she didn’t stipulate that specifically.

By now, everyone is probably aware of the element of coercion that so often plays a role in the sexual politics of Greek myth. By modern understanding, what Selene does to generate fifty offspring by an unconscious partner would be considered sexual assault. However, it would have only been unusual to the Greek’s in terms of the gender reversal of who is doing the coercing, but since Selene is a goddess and Endymion a mortal, it’s fair game. This story reminds me distinctly, and I wonder if there is a trace connection, of tales of the medieval succubus…a female entity who preyed upon unsuspecting men – often by seducing them in their sleep. (which also would be a convenient way to explain unsanctioned nocturnal activities…*cough* “The succubus made me do it!” ).

Roman Sarcophagus – 2nd century AD

Source

In later Roman antiquity the story of Selene and Endymion preserved all of its somnolent eroticism (note all of the little winged babies on the image above…they are Erotes (Amores in Latin), clear indicators that love is afoot.) but the persistent notion that Endymion never died, but rather was eternally asleep also made depictions of this story very popular on funerary pieces like the sarcophagus above.

Fragment of the group of Selene and Endymion.

Marble. Roman, after a Greek original of the 2nd century B.C.

Inv. No. A 23.

Saint-Petersburg, The State Hermitage Museum.

Source

There is something really compelling to me about images of the sleeping Endymion. He is always depicted as powerfully masculine, yet in sleep, he is also vulnerable. The sculptural fragment above also conveys a kind of latent eroticism with his arm raised above his head, leaving him open and exposed and perhaps even inviting to Selene’s amorous advances. As usual, I didn’t have to look terribly hard to find some equally enticing Armitaganda…

Lucas North sleeps…

Spooks 8.5

Source

Guy of Gisborne sleeps…fitfully

Robin Hood 3.6

Source

As Keats said in his poetic Endymion:

A thing of beauty is a joy forever…

I was digging through some pictures in my cleverly disguised Richard Armitage folder when I came across this one…a favorite despite the copious costume blood:

John Porter (Richard Armitage) Strikeback Behind the Scenes

Source

Look at Richard Armitage going all contrapposto!!

The art aficionados in the crowd will recognize this term as coming from the artistic tradition of the Italian Renaissance. It translates loosely to “counterpose” and refers to the body position where the weight is shifted onto one leg, turning the upper body slightly off-axis from the hips and legs. Overall, it is a position that produces a figure that looks immediately more relaxed.

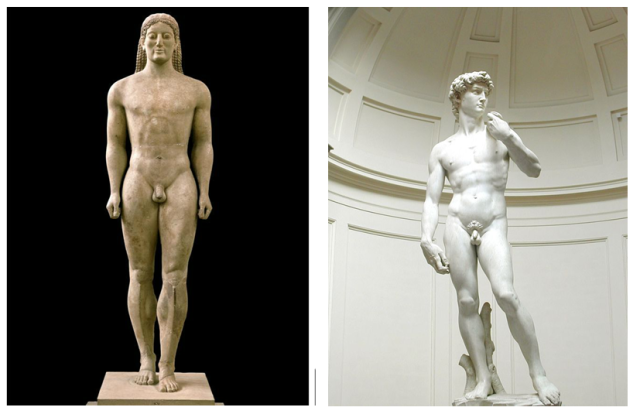

Even though the Anavysos Kouros on the left is to be understood as stepping forward, he appears stiff and static when compared to the mature Renaissance contrapposto style of Michelangelo’s David on the right. Although both of these pieces are sculpted in marble and obviously immobile, they serve to illustrate the other hallmark visual effect of contrapposto – implied movement. It seems almost inevitable that David will eventually shift his weight to the opposite leg, while the kouros appears perpetually frozen mid-stride.

What is fascinating to me is that although nearly a millenium elapsed in style and time between David and the Anavysos Kouros, the earliest known example of contrapposto is much closer to the kouros tradition than the Renaissance one. The Anavysos Kouros dates to around 530 BC. Less than fifty years later, the Greeks would embrace a very different sculptural style in a piece called the Kritias Boy

The Kritias Boy is an enormously important piece of sculpture for a number of reasons…one of them being that he is the earliest known example of the contrapposto technique and as such, marks the transition between the Archaic and Classical styles of Greek sculpture. His remarkable provenance provides secure evidence for a relatively narrow dating window for the emergence of this style in Greece. …

WARNING….short historical divergence imminent 3…..2…..1…..

The armies of the massive Persian Empire, led by Darius the First, invaded Greece in 490 BC in reprisal for what they considered Athenian interference in Persian domestic affairs. The Greeks, especially the Athenians, were scrambling. It seemed almost inevitable that Persians’ vastly superior numerical advantage would win the day. However, owing to strategic and tactical decisions made by the Athenian commander Miltiades, tiny Athens defeated the Persian force at Marathon which led to Darius’ retreat not long after.

This was a humiliating, but only temporary setback to the Persians, who immediately started ten years of planning for a massive land based invasion of the Greek mainland which would eventually be led by Darius’ son Xerxes. When Xerxes marched into Greece in 480Bc, he had a massive ax to grind against the Greeks…especially the Athenians. After the famous last stand of the Spartans at Thermopylae, Xerxes (who, contrary to his depiction in 300, was not a ten foot tall giant pierced in every possible point) marched swiftly to Athens where he sacked the abandoned city and burned it to the ground…the sacred precinct of the Acropolis included.

Kritias Boy – Located in the Acropolis Museum in Athens – my shot (note the human figures for scale)

And, we’re back. Long story short, the united forces of the Greek poleis repelled this Persian invasion as well, and by 478 BC, all that was left was to clean up the Persians’ mess. Here’s where the provenance of the Kritias Boy comes in. All of the materials on the Acropolis were considered sacred objects, so before the Athenians could rebuild from the Persian destruction, the sacred objects needed to be properly disposed of. This disposal took the form of a massive bothros, or sacred dump dug along the slopes of the Acropolis in which the sanctified materials were buried. This provides a terminus ante quem (date before which) for the sculpture…that is, we know that he must date to before the Persian sack of Athens in 480 BC. Stylistically, we also know, by comparing him to every other sculpture in the typology leading up to him, that he cannot date to much prior to 480 BC either. It is pretty clear that he was installed on the Acropolis very shortly before the Persian sack.

The utilization of contrapposto is clear in the tilt of his hips and the subtle torsion of his upper body. It is even more evident in the rear view

Kritias Boy Rear View

Acropolis Museum Athens

My Shot..(yep, I stood there and waited until people cleared out of my immediate frame so as not to distract…I’m patient that way!)

Here the shift of the weight onto one leg is obvious in the relative positioning of the buttocks. We can also observe the very subtle “S” curve of the upper body. In all, it is a much softer, much more naturalistic pose than what was popular in the Archaic period. This style went on to become ubiquitous in subsequent periods.

John Porter in contrapposto above is not alone in the Armitage oeuvre. I thought you might not object to a brief overview…but first, Guy of Gisborne illustrates “assuming” the contrapposto position:

Another John Porter favorite

Lucas North contrapposto from behind

Lucas is “wearing” John Porter’s thighs here…

http://www.richardarmitagenet.com

The leather contrapposto stylings of Guy of Gisborne

And more recently, Richard Armitage himself at CinemaCon

This is by no means an exhaustive list…you may have noticed that I’ve left out a spectacularly good example of Guy of Gisborne…or maybe you didn’t. Can you find it? Happy contrapposto hunting Armitageworld!

Now don’t get me wrong, I have been LOVING all of the intel coming in from people who’ve been seeing Richard Armitage in The Crucible in London, but I thought I might mix it up a bit (not to mention that I haven’t had the brain space to do that comparison between The Crucible and Greek Tragedy) I’m returning to the familiar theme of showing you one of my favorite bits from the Classical Tradition…well, sort of, since these particular bits predate the classical world by at least two millennia. But what the he$$…it’s all ancient to you right?!

“Canonical” Female Figurine

Source

The figurine above is one example of a large body of similar sculptures which come from the Cycladic Islands of the Aegean Sea. They are known collectively as Cycladic Figurines. Examples of this type date to the middle of the third millenium BC. They are usually sculpted in local marbles and range in size from a few inches up to a few feet tall. I’ve always been attracted to the minimalist, stylized nature of these pieces. There is no doubt that they are meant to be understood as human figures, but the style leaves most of the details of the human form to the imagination.

Truthfully, a lot of our understanding of these figurines is rather murky. The ones with known provenance were found largely in tombs, suggesting some sort of funerary function. However, when mimimalism became vogue in the Western artistic aesthetic in the mid 20th century, these figurines became highly popular among collectors. This popularity spurred a flourishing black market for the figurines which was supplied by looting. Estimates are that 85% of the examples in museums today come from insecure contexts, and without this contextual information, we are unable to say much with certainty about these sculptures.

We can deduce a few things from the figurines themselves. Like the example above, the majority of these figurines are female – the emphasis on the breasts and pubic area of the figures is clear. In fact, earlier examples bear a striking resemblance to so called “Mother Figurines” like the “Venus” of Willendorf which occur from the later Paleolithic throughout the Neolithic period.

The exaggerated physique with emphasis on the breasts, hips and pelvic area has long been hypothesized to indicated a connection to fertility and fecundity. The Cycladic example is still heavily stylized, but the component parts are noticeably similar. The later examples (like the one above) are even more stylized, but on a figurine that has so little detail, the breasts and a clearly indicated pubic region stand out. This has led many scholars to hypothesize that like the earlier “Mother Goddesses,” many of the Cycladic figurines had some sort of fertility function. It is a compelling argument, but of course in the absence of a written record or information from the original context, it is virtually impossible to say this, or anything else with much certainty about these enigmatic sculptures.

I’ve said that the majority of these figurines are clearly female, but there are some that are male. Although a few of the male figurines are engaged in activities…there’s a harp player and a flute player…the majority of them take the typical crossed arm pose.

I’ve always loved these figurine… I’ve worn Cycladic head earrings, I’ve given replica Cycladic Figurines as gifts. In a city littered with museums of ancient and modern art, the Goulandris Museum of Cycladic Art is one of my favorite haunts in Athens. And thanks to Servetus, who noted what is now so clear to me, I have a new reason to love them – they bear a stylized resemblance to another favorite of mine,

Sir Guy of Crossed Arms S1

Source

Sir Guy of Crossed Arms S3

Source

I guess I’ve always had a thing for the long and lean…even in sculpture. (There’s also a certain a beautifully angular shared facial feature.)

Welcome to another installment of the Ancient Armitage tour through some of my favorite pieces of Greco-Roman art. I’ve made no secret about having a certain preference for the art of the Hellenistic period, so I doubt anyone will be shocked when I reveal that another of my faves belongs to that period.

“The Dying Gaul”

2nd cent AD Roman copy of 3Rd cent BC original

Source

This Roman copy in marble is modeled after an original Greek piece, probably cast in bronze, that was commissioned for the king of Pergamon to commemorate his victory over neighboring Galatia – populated by Celtic or Gaulish peoples. The sculpture depicts a mortally wounded Gallic warrior, identified by his mustache and torc, as he lies, slumping down among his weapons. If we look closely, we can see the mortal sword wound just under his right pectoral.

Unlike similarly themed works from the 6th and 5th centuries BC, the severity of his wound is evident in his posture and expression. The viewer can almost feel the valiant effort the wounded warrior is exerting to stay upright as the weight of his pain bears him down. While the ancient Greeks were exceptionally good at trash talking their enemies (cf Herodotus’ The Histories where the author goes to some length to describe the surpassing oddity of most things Persian) they are also exceptionally skilled at depicting the enemy as noble and strong, even in defeat. Makes sense…after all, it wouldn’t be much of a victory if the enemy were ignoble and weak specimens.

Hellenistic art is often emotionally evocative, and the pathos of this piece is particularly striking to me. In Greek, πάθος in general terms means “that which happens to a person or a thing,” and it also takes on a more specific connotation of suffering or misfortune. The Dying Gaul’s suffering and misfortune is clear from the heavy, slumping position of his body and is further enhanced by his expressive face.

The bowed head with it’s furrowed brow, pensive eyes and slightly open mouth present a fallen warrior determined to endure his suffering stoically, but unable to wipe all trace of it from his features.

Pathos is also an interesting word in the sense that it comes into contemporary English usage as an element of communication. As originally articulated by Aristotle in Rhetoric, pathos is a device used to appeal to an audience’s emotions. Richard Armitage is quite adept at playing with this quality in any number of his characterizations by means of a variety of verbal cues, but like The Dying Gaul, he is also able to tap into the power of pathos through purely visual means…

Whether it’s Guy of Gisborne’s excruciating interchanges with Marian or the Sheriff,

Guy of Gisborne – S2 Source

Paul Andrews desperately trying to keep his secret

Between the Sheets Source

John Thornton facing financial ruin,

North and South – E4

Source

Lucas North’s anguish in the face of all that he’s lost

Spooks S7 E2 Source

John Porter’s grief

Strikeback S1 E6

Source

or the heavy burden of Thorin’s duty,

the ability to visually evoke the powerfully emotive qualities of pathos is something that Richard Armitage and The Dying Gaul share.

~~~~~~~~~

PS…I would remiss if I did not share the following gratuitous rear view: